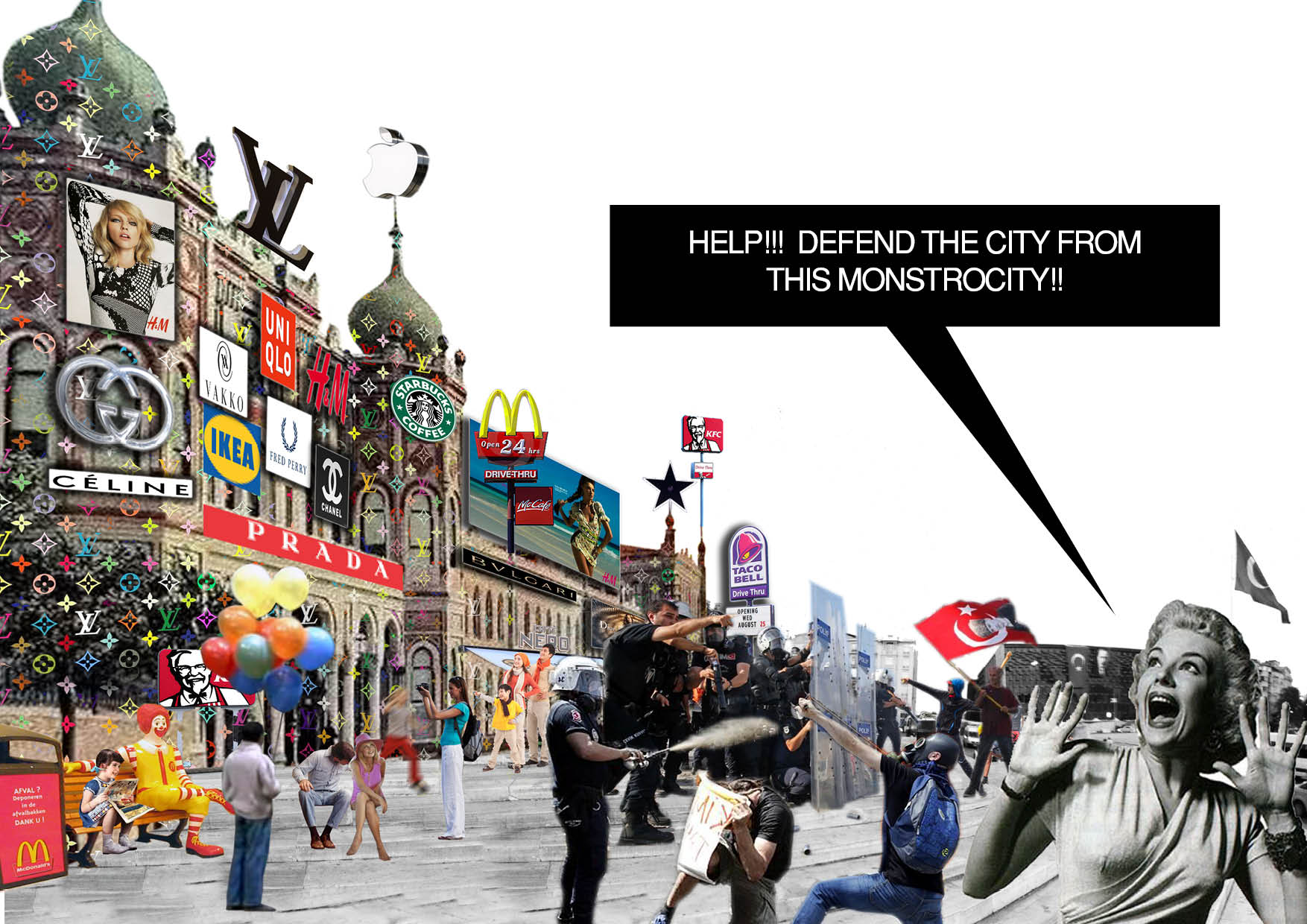

Over the past several months we have witnessed outside of our office window facing Taksim Square the repeated confrontations between the protestors and government riot police. What began as a peaceful demonstration against the destruction of Gezi Park by a few hundred environmentalists on May 30th of 2013, soon turned into a nationwide protest against the increasingly autocratic nature of Prime Minister Tayip Erdogan’s AKP. It became clear that what seemed to be an isolated incident was in reality the final straw for the people fed up by the government’s forceful positioning on multitude of issues ranging from censorship, regulation of alcohol consumption, police brutality, and urban renewal projects in the likes of Gezi Park and Taksim Square.

- Date: 2014-02-10

- Client:

- Program: Urban Planning, Research

- Team: OCX Luke Willis, Esin Erez, and Tobias

- Location: Istanbul, Turkey

- Status: On going

TAKSIM SQUARE 1 : 200,000

At 1 : 200,000 scale, Taksim Square and Gezi Park appear as a speck of dust in comparison to the vast expanse of 5,343 square kilometers that is Istanbul. However, the significance of the square and park can be highlighted when mapping out key information from the city.

Istanbul strides between two continents divided by the Bosphorus, which connects the Marmara Sea to the Black Sea. On both sides of the Bosphorus the topography is characterized by steep hills that emerge out of the sea. Due to this demanding geography Istanbul’s primary public transportation system is a complex network of metro lines, trams, buses, metrobuses, ferries, and funiculars. Taksim square is at the epicenter of this network linking the various modes of transportation. It is the central transportation hub hosting over a million commuters a day.

“UPON THE MARMARAY’S COMPLETION, RAIL USE IN THE CITY IS EXPECTED TO INCREASE TO 28 PERCENT (FROM JUST 4 PERCENT), BEHIND ONLY TOKYO AND NEW YORK CITY.”

In 2013, the Marmaray tunnel was inaugurated as the first railway connection to link the two sides of the city. Consequently, Taksim Square can further anticipate an increase in its use and prominence. It can therefore be seen that the city is growing outwards in reference to Taksim Square, as it continues to grow supporting the ever-increasing migrant population.

PARKS:

Gezi Park stands as a modest size park at only 38,000m². While, this may seem an insignificant size when seen in the scale of the larger city, it is easily noticeable that it is one of the very few inner city parks that exist. To the naked eye, Istanbul appears very lush and green especially if you look at the vast rolling hills on the northern areas. However, according to the research by American Standards, for the 14.1 million residents of Istanbul there are only 2470 recreational areas, which is a mere 1.53 m² recreational area per person.

Not only is this lower than the recommended 10sqm/person, it is significantly less In comparison to the major cities across Europe. Highlighted by the Unit Park Area Ratio, Istanbul’s 1.53 m²/person is belittling compared to the 27 m²/person for London, 45.5 m²/person for Amsterdam, and a whooping 87.5 m²/person in Stockholm. The European Green City Index also confirms that Istanbul needs to reconsider its environmental policies as it ranks 25th out of 30 European cities.

Kerem Ateş, the general secretariat for the Turkish Environmental and Woodlands Protection Society, or TÜRÇEK, points out that green areas in Istanbul were being marked for construction through rapid zoning changes in recent years.

"THE GREEN SPACES OF ISTANBUL ARE ABOUT TO BECOME EXTINCT. ISTANBUL IS PRACTICALLY BEING LEFT WITHOUT OXYGEN. THERE IS A GREAT EFFECT FROM THE LACK OF TREES AND UNCONTROLLED URBANIZATION IN THESE SUB-SAHARAN TEMPERATURES EXPERIENCED IN SUMMER."

SHOPPING MALLS:

Istanbul got their first fix of mass scale consumerism in the form of a shopping mall when Atakoy Galleria opened in 1988. Since then the total number of shopping malls in Turkey has grown from a modest 106 in 2005 to a staggering 334 in 2012 and is expected to surpass 400 by sometime in 2014. This will put Turkey, a country with a population of 74million, at par with the total numbers of shopping malls in the US, which has a population of 314 million.

The advancement of Internet shopping and a sheer excess of retail properties has seen the US shopping mall typology in decline, as indicated by the fact that there has not been a new shopping mall built since 2007 with the exception of one in Salt Lake City. In contrast, the number of malls in Turkey has risen by 400% since 2002 and Istanbul alone already accounts for around 180 shopping malls.

TAKSIM SQUARE AT 1 : 5,000

When one exits Taksim Metro station they are typically lost, not knowing left nor right. A series of tunnels and escalators meander until finally leading up to a set of stairs to an open space that is Taksim Square. The Square is characterized by a large Turkish flag, a dilapidated modernist building, a single towering hotel, a small memorial sculpture, and a park hiding behind a set of stairs. But in the larger context, you are stranded on a giant traffic island. You are surrounded by hundreds of cars, buses, and a tram, without an obvious crosswalk nor passage for the million commuters. This leaves every visitor helplessly disoriented and puzzled wondering if in fact Taksim Square is a square? A park? A monument? a hub? a culture center? a historical artifact? or simply a large roundabout?

“SO, HOW GRAND IS THE ENTRY TO THE CITY CENTER THROUGH TAKSIM SQUARE?”

In order to decipher this absurd entrance and center to the city we zoom into 1 : 5,000 scale. At 1 : 5,000, Taksim Square and Gezi Park become visible on the map and can be understood in the context of its neighborhood. It is at this scale that the transformation of the city can be witnessed through the changes that have taken place historically. By looking at the significant developments that took place in this area through various periods one can interpret the forces that have shaped the Square in its current form and function. It is only through this means that we can begin to comprehend the spatial, architectural, political, mess that it is in now. And, whether Erdogan’s claim to restore the Ottoman Barracks is indeed a necessary act to preserve “history.” In the following, we will take a look at the five distinct periods by which Taksim Square and its surrounding area was sculpted by.

1700-1800

The history of Taksim square reaches back to the 17th century, when it was known as the Grand Champs des Morts (The Great Cemetery), since it contained Armenian, Christian, as well as Muslim cemeteries. It was a popular promenade and picnic area. Maksem, the water reservoir built in the 18th century, was located at the edge of what was the limits to the city eventually gave Taksim its current name for the area.

1800-1900

In the 19th century cemeteries were removed to make place for military buildings, including the Topcu Kislasi(Artillery Barracks), Taskisla (Stone Barracks), and the Gumussuyu military hospital, . The area in front of Topcu barracks was used as Talimhane(drill grounds,) and the Taksim Gardens were created at the north side of the Topcu Barracks, the first example of its kind in Istanbul, and a popular recreational area for the Pera population.

1920-1930’S

By the time the new Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, the Topcu Barracks had lost its military function and remained unoccupied until the public reclaimed it as a sports arena for football matches, horse races, wrestling tournaments, and other public entertainment. The Republic Monument had been erected in 1928 depicting Ataturk and his comrades dressed in modern, western-European clothing, symbolizing the contemporary outlook of a new Turkey. Taksim was built to provide its citizens a space to showcase what the newly founded Turkish Republic was made of, and also as an inauguration to the larger urban regeneration plan to be created by Henri Prost.

1930-1970’S

Due to the shifting of state funds to create a new capital in Ankara, restoring the Barracks was never carried out. More importantly, Ataturk wanted Istanbul to reflect the modernized, western influenced ideals of the new secular republic. To achieve the new outlook for the future for a new Republic, Henri Prost was appointed to devise Istanbul’s redevelopment plan between 1936 and 1951. As part of this plan, the Topcu Barracks were demolished in order to create Gezi Park as a green public space. Talimhane, Mete avenue, and Gumussuyu area next to it were developed into residential areas. And finally the Ataturk Cultural Center (AKM) was planned as a cultural center, an opera house, and most significantly as the contemporary monument to Taksim Square and a modernist icon for Istanbul.

1970-2000’S

By the time the Ataturk Cultural Center (AKM) was built in the 70’s, Henri Prost’s original urban plan to create a central axis in an otherwise spineless Istanbul had been long abandoned. Prost’s master city plan provided for a much larger continuous green space, which he called Park No. 2, covering an area of 30ha between the neighborhoods of Taksim, Nisantasi and Macka extending to Bosphorus including the Dolmabahce Valley. The larger park which was intended to offer green space for recreation to Istanbul’s residents and tourists, was discarded in favor of selling the public land to private interests. Similar urban plans that had come into existence after the war were also altered to allocate larger swathes of the planned public park areas to private hotels such as the Hilton, the Marmara, Divan, Hyatt, Swissotel, and Ritz Carlton. Even Gezi Park, which was already built was subject to losing its outlying zone by the construction of the Ceylan Interncontinental Hotel.

- 2014

The Taksim neighborhood is currently characterized by the many layers of development that has taken place in the past 200 years. Throughout time, the area has repeatedly redefined itself as master plans have been implemented and abandoned continuously. What was once the Grand Cemetery at the edge of the city has become the central transportation hub, square, and a cultural/symbolic destination for a “New Istanbul.” But it still remains also as a residential housing area, a hotel district, a commercial center, and a dilapidated park.

Currently, retail shops and office spaces have gentrified the area along the major streets, while residential areas have been pushed back behind the artery roads. Hotels are ubiquitous as the number of tourists increase every year, but the skyline has been untouched since the international hotels defied the zoning codes by buying their rights inside the planned public park #2. Cultural and Educational facilities are precariously scattered along the abandoned master plan. Finally what remains as the public park is disconnected, discarded, and are frequently occupied by stray dogs on any given day.

The context of Taksim square is amorphous. It’s identity, function, and use perpetually undefined. This is precisely the reason why it is so confusing stepping out of the metro station. But also a fact for PM Erdogan to implement a “Neo-Ottoman” development to manifest his new vision in the heart of Istanbul.